“As I followed the winding track of the mossy road that led us out of the woods for a final time that day, I stopped frequently to examine the winter buds. I ran my fingers along the plump green buds of the sassafras; …the slender, spearhead shapes of the beeches; the blunt, velvety buds of the shagbark hickories. Within each, folded and tucked and compressed like a packed parachute, was the leaf of another summer..” ~Edwin Way Teale, Wandering Through Winter, ©1957

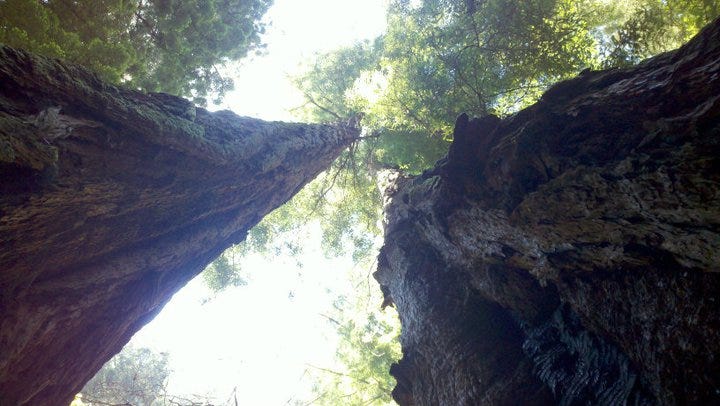

Two coastal redwood trees, hundreds of feet tall, stand just feet apart in the center of Cathedral Grove in the Muir Woods National Monument north of San Francisco. Seemingly two separate trees, they likely share an unseen root system that unites them below ground. Redwoods do not thrive alone, but rather in stands to support each other’s growth. I linger between these trees, my arms outstretched, face tilted toward the sky. Sun speckles flit between the leaves and branches that form the canopy high above.

Grateful that no other park visitors come along to disturb my time in this space, I stand between the trunks and see that each has a symmetrical hollowed-out section mirroring the gap in its companion tree. It appears as if something used to exist in the center, at the base of each trunk, which is no longer there. A small wooden railing erected between them on the far side keeps people from wandering down the embankment to the stream. The construction resembles a rustic altar in a space more serene and holy than any church I ever visited.

About twenty feet away, the elevated boardwalk made of repurposed fallen redwood splits around a grove of trees and ferns. I hear voices, and two young women soon approach. I step out of my newfound sanctuary and offer to take their photograph. Soon, another small group arrives to admire ‘my’ spot. Crowds attract crowds, and within minutes many park visitors fill the area. Farther down the path sits a small bench where I wait for the crowds to disburse and the silence to return.

When they move on, I return to my trees and crane my neck to try to see beyond the canopy high above.

“If I ever get married again, this is where I want to say my vows,” I say aloud, resting my face against the rough bark of the massive redwood to my right. A little rodent, maybe a mouse, rustles in the leaves beyond the railing. Water spills over rocks in the stream. Sun rays spray through the leaves, filling the hollow space.

As awe-inspiring and majestic as I find the trees of Muir Woods to be, occasionally I look down long enough to comprehend that some fall.

For some, winds wrestle them from the earth leaving roots exposed. Others fall in jagged shards, broken near their base. Massive trunks, resting across small gullies, thread through other trees, or prop against hillsides. Often, when one tree falls, it takes several others with it, all crashing to the ground.

When redwoods die or topple, a vast opening is created in the forest canopy causing more light to reach the forest floor. Flowering plants, such as azaleas, spring to life under the sun’s warmth and the fragrant scents attract insects and birds. Bright blooms lure butterflies and other small creatures. New trees sprout, including small redwood saplings trying to gain height and position.

The sky resembles a thin, nearly translucent silver veil blanketing the branches of the canopy. As rays of warm sunlight burst through to the pockets of red earth left behind by felled trees, they illuminate dew particles lingering in the air. I hurry ahead on the path to a warm spot in the light — a welcome refuge from the damp cool shadows.

If a redwood is struck by lightning, a portion of the inside is blackened and burned out by the electrical current. Yet the tree usually does not die. The outer layer of bark, which can be six to twelve inches thick, replenishes the upper branches with nutrients absorbed from the ground. Although the charred interior is permanent and sometimes reveals gaps large enough for a person to stand within, the tree continues to grow.

I pause by a tree bearing the scar of a lightning strike. Its outer layer of bark reveals the charcoal-like inside the way a theater curtain might peel back offering a glimpse backstage before the show begins. Inside, the tree appears as firm as granite except for a few jagged edges delicate enough to snap. With my legs pressed against the wooden railing separating the path from the trees, I lean forward reaching my hand towards the tree’s wound. It is still inches beyond my fingers.

When just the upper regions of redwoods are damaged, they heal through a process called reiteration. The tree sprouts new limbs from just below the break. As that new growth reaches past the point of injury, branches often fuse forming hammock-like areas made of leaves and smaller twigs — an entire new canopy of life hundreds of feet above the ground.

Fire. There is a line, north of which redwoods do not grow because the summers are too cool and wet to allow for forest fires, which are necessary for a healthy forest system. Fires clear away dead brush and accumulated matter that clogs the forest floor, preventing new growth. After a fire, new seeds take root, saplings grow, native plants thrive, banana slugs and butterflies return, along with all manner of animals and plants that thrive within the forest, and allow the forest to thrive.

Redwoods have the capacity to survive fires. Fire helps them more than it hurts.

Another casualty lies farther down the path. Its bark cracked in long planks yet the center is intact as far as I can see. New green shoots, lichens, and ferns, spring within the bark and a few small birds hop along the trunk, pecking at insects.

I close my eyes, listen to the birds, and inhale the scent.

It takes a few moments to place it; that scent.

During my husband’s burial service, a mound of black dirt waited next to his grave. We placed ivory roses on his mahogany casket before they lowered it into the ground. The funeral director raised his eyebrows as if to ask permission to conclude the ceremony. I nodded.

As the workers gently moved the damp clumps of earth with their shovels, the ivory petals vanished from sight.

I enjoyed reading about the redwoods, I visited Muir Woods many years ago (probably I was nine at the time!). Here in Scotland, we have the John Muir trail, starting from his birthplace in Dunbar on the East Coast.

You write beautifully of the power in a redwood grove.