Every morning, I look up at the tips of the tree branches. I’m waiting for that spring green flush I mentioned a couple of weeks ago. Seeing trees like mine just a few miles away that are already beginning their seasonal burst, I wonder with more intent curiosity, what makes tree buds open when they do? I was looking for more depth than the obvious fact that it is warmer and brighter.

These are the questions for which a Google search was made!

My initial query provided some fancier and more scientific words than “warmer and brighter,” but the gist was the same. As I clicked and read, I found the new-to-me term: phenology.

“Phenology is the study of the timing and cyclical patterns of events in the natural world, particularly those related to the annual life cycles of plants, animals, and other living things.”1

(Incidentally, one of my lottery dreams is to pursue successive master’s degrees for the rest of my life… Phenology!)

I’ve been amateur phenologizing since moving to my forest nearly nine years ago. Being fully surrounded by nature has shifted the way time moves for me. Every day reveals a shift in the trees, flowers, insects, birdsong…the smallest of details constantly changing and revealing. The pandemic further slowed time and heightened my appreciation for the natural world's cycles. I think that happened for thousands of people who turned to nature to soothe, keep company, and escape the maddening day-to-day.

Those pandemic days saw an explosion of interest in backyard birdwatching. Four years later, what may the migration patterns of ruby-throated hummingbirds or sandhill cranes tell us about our changing world? Or the beech tree buds and Dutchman’s breeches that line trails of the Eastern and Western Highland Rim in Tennessee? What may the black vulture family in my barn reveal in these five years they’ve been present? How might today’s observations, compared to those of 20-30 or more years ago, inform our thinking, inventions, health, and economies?

Phenology was prevalent in ancient times and among Indigenous cultures as a practice of observation long before the word existed. In 1736, English naturalist Robert Marsham wrote “Indications of Spring”, a series of 27 records documenting everything from breeding activity, birdsong, toads, flowering dates, and so much more.2 Yet, it wasn’t until December 1849 that Belgian botanist Charles Morren first used the term phenology in a public lecture. Four years later it appeared in his published work.

There are abundant scholarly articles and studies by professional phenologists documenting worldwide changes in bird migration and trends in tree leafing dates, for example, that underscore the realities and impacts of climate change. And thousands more people working in adjacent and impacted professions on creative solutions and meaningful policies. I know some of those folks…they have my awe and gratitude.

But what about the rest of us? The amateur phenologists? The everyday phenologists? Can our observations and data records matter beyond fulfilling our own curiosity?

Well…YEAH! (It would be quite the plot twist if I said otherwise.)

Have you heard of citizen science?3 In short, it is a method of crowdsourcing scientific data. We all can submit information about our observations that may help inform understanding and decision-making nationally or globally.

How? I’m glad you asked! Here are a few options:

Remember the Great Backyard Bird Count I wrote about earlier in February?4 That’s a perfect example of crowdsourcing important information with just a 15-minute time commitment. Keep an eye on future dates.

Those thousands of new birders in recent years…many are also contributing data to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and we can too!5

Those tree buds I’ve wondered about…explore Project Budburst, a program of the Chicago Botanic Garden.6

And, as I just discovered, there is the National Phenology Network and its Nature’s Notebook app for all of us everyday phenologists.7

The forever-student and Girl-Scout-patch-earning learner in me is giddy about their opportunities to “become a certified observer and earn badges.” Get ready, NPN; here comes five years of black vulture data!

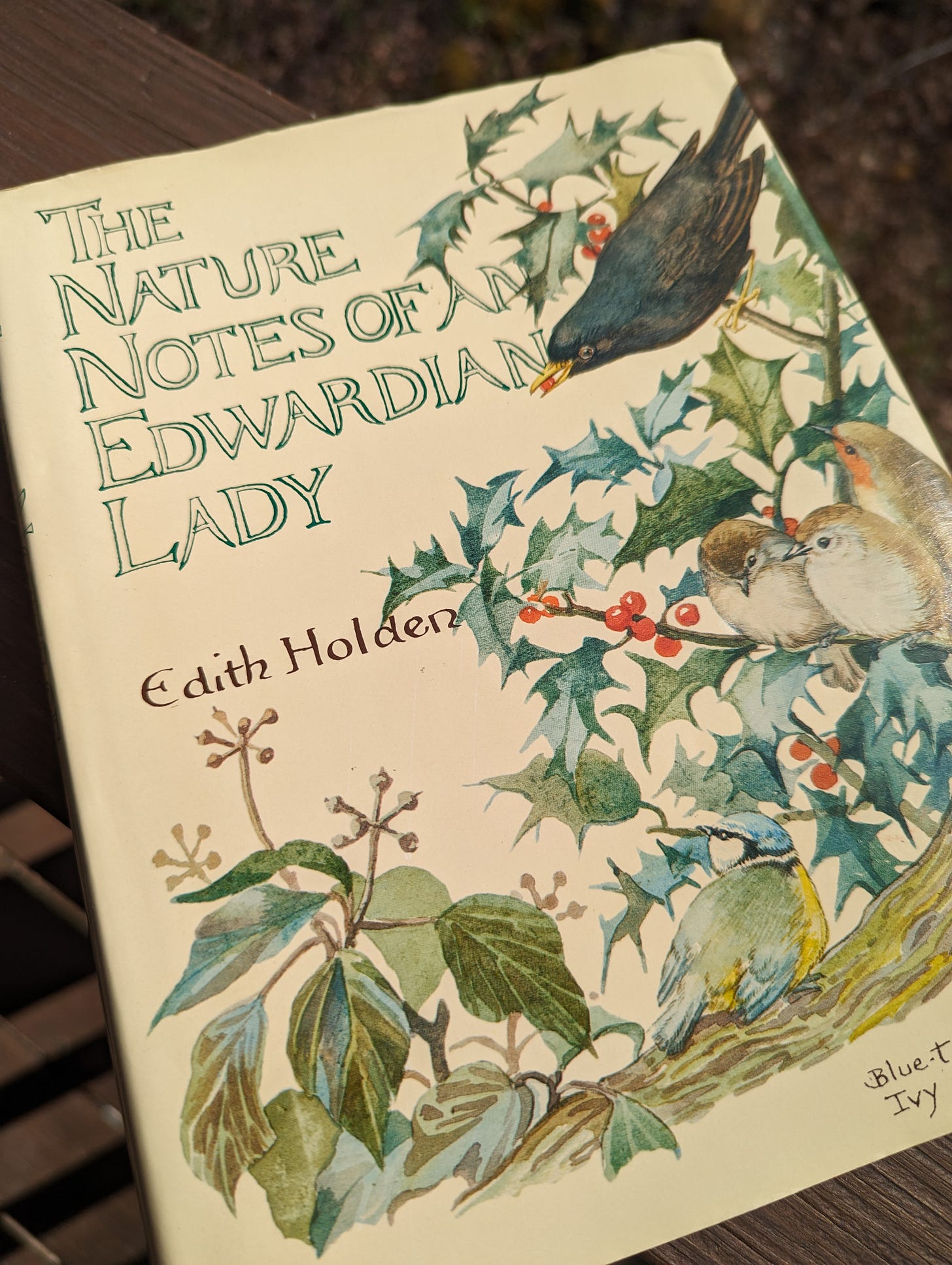

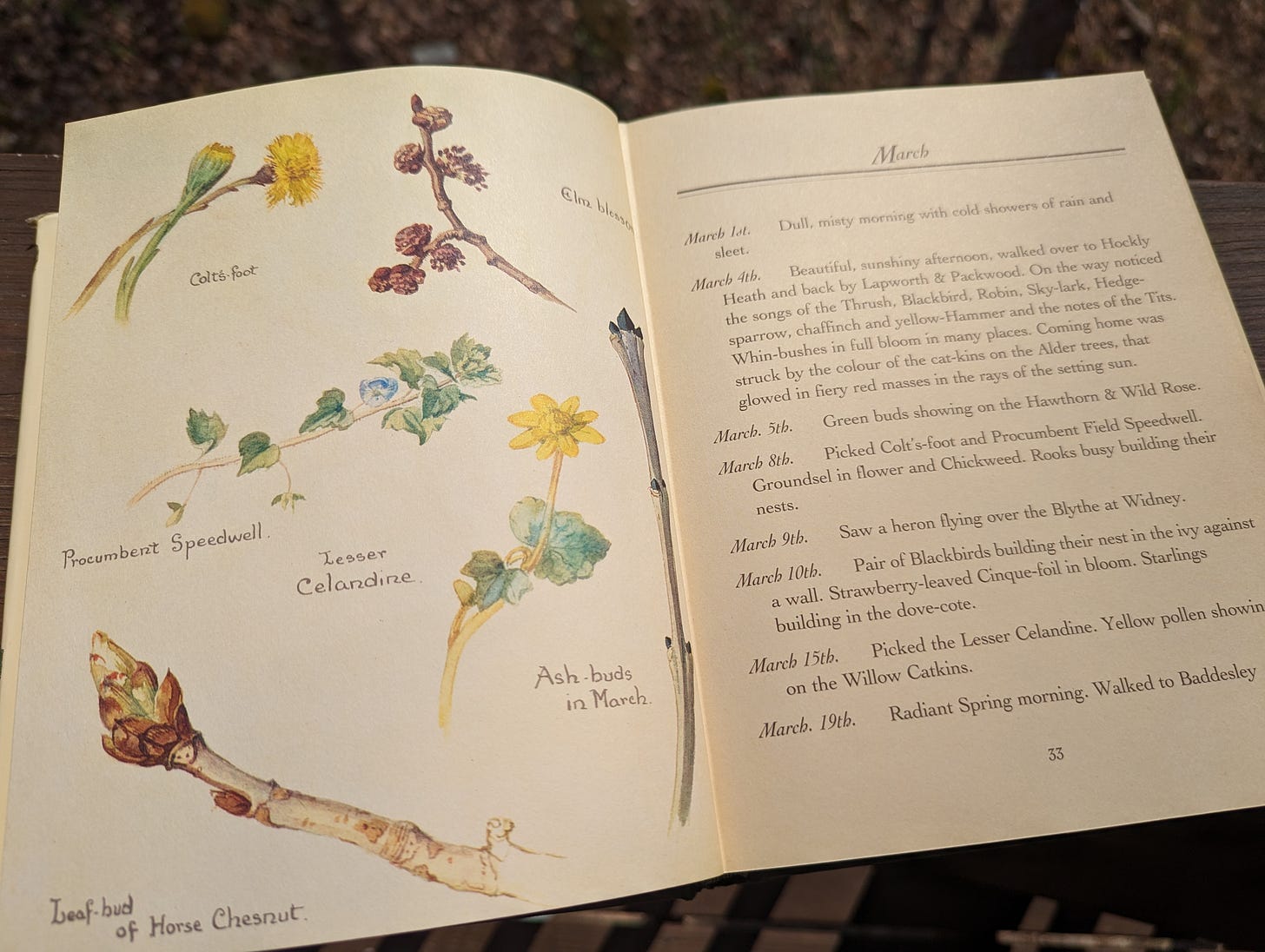

Currently Reading

…And…

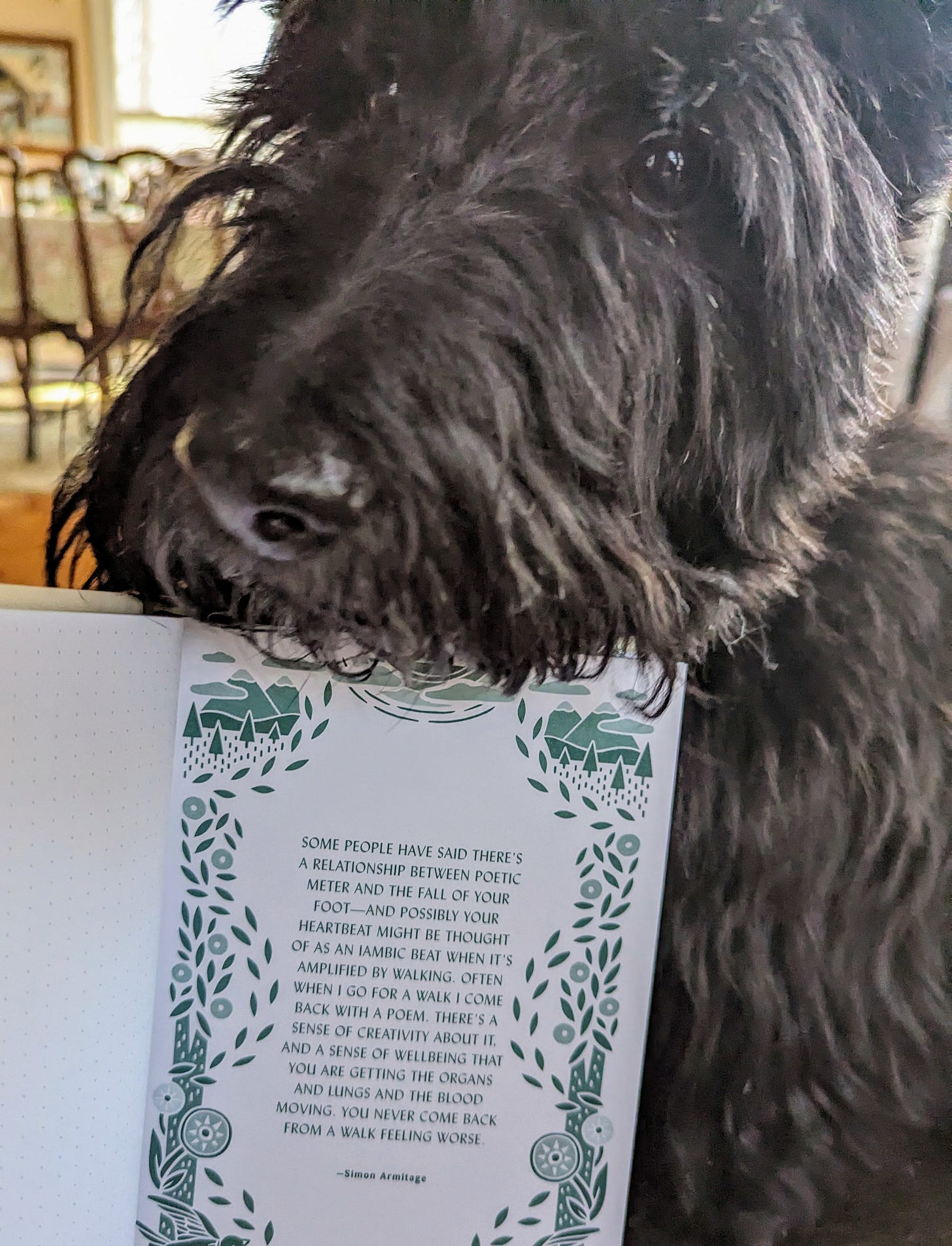

Just four minutes…

Let’s try some extra credit this week. How about four minutes each day…observe the same tree or bird feeder or garden bed. You choose the spot and time of day. Observe for four minutes and note what you see.

Journaling prompt…

Keep writing about what you see, hear, smell, and feel in these early days of spring.

Or return to journals from past years for ideas to pursue.

…see where it leads you.

If you enjoyed this week’s edition of “A Curious Nature”, I hope you may choose to subscribe, drop your thoughts below, click the heart, or share with a friend.

Thank you!

https://www.usanpn.org/about/phenology

https://www.citizenscience.gov/#

https://www.birdcount.org/

https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/

https://budburst.org/

https://www.usanpn.org/

I was just thinking and writing about this too. Everyone talks about Tennessee's "little winters" (Blackberry, Dogwood etc) which can sound a like an old wives tale but is actually a result of data collected by people from these types of historical observations.

This post reminds me of a concept I learned about for the first time last year. In the ancient Japanese almanac, there's 72 micro-seasons, which are 5-day seasons centered around natural cycles of animals and plants. https://www.kyotojournal.org/uncategorized/the-72-japanese-micro-seasons/